Works by this Artist

Women of AlgiersEugène Delacroix, 1834 Barque of Dante

Eugène Delacroix, 1822 Liberty Leading the People

Eugène Delacroix, 1830 Massacre at Chios

Eugène Delacroix, 1824

Background

son of Charles Delacroix, politician and diplomat (during French Revolution)

Studies

Lycée Imperial in Paris (1806-15); with Pierre Guérin (1815); Ecole des Beaux-Arts (1816)

Career

1822 - Salon debut with Barque of Dante (purchased by the French government and exhibited at Luxembourg Museum, Paris; now at Louvre)

1824 - Massacre at Chios exhibited at Salon, purchased by French government

1830 - awarded Legion of Honor medal for Liberty Leading the People

1833-40 – state commissions for mural decorations at Salon du Roi in Palais-Bourbon (1833); library of the Chamber of Deputies (1838); cupola of the senate library, Luxembourg Palace (1840)

1848 – co-president of General Assembly of Artists

1855 – exhibits 35 paintings at Exposition universelle, Paris

1857 – elected to Académie des Beaux-Arts on 8th attempt; begins teaching at Ecole des Beaux-Arts

1859 – final Salon exhibition

Travels

England (May-August 1825); Spain, Morocco and Algeria (January-July 1832)

Commissions from

French government; Ferdinand-Phillippe, Duc d’Orléans; Duchesse de Berry; Louis-Philippe (King of France)

Important Artworks

Death of Sardanapalus, 1827 Salon (Louvre)

The Natchez, 1835 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1861 Fresco (St Sulpice, Paris)

In a 20 October 1853 diary entry Delacroix speculated about the power of painting:

“The type of emotion peculiar to painting is, so to speak, tangible: poetry and music cannot give rise to it. In painting you enjoy the actual representation of objects as though you were really seeing them and at the same time you are warmed and carried away by the meaning which these images contain for the mind. The figures and objects in the picture, which to one part of your intelligence seem to be the actual things themselves, are like a solid bridge to support your imagination as it probes the deep, mysterious emotions, of which these forms are, so to speak, the hieroglyph, but a hieroglyph far more eloquent than any cold representation, the mere equivalent of a printed symbol. In this sense the art of painting is sublime if you compare it with the art of writing wherein the thought reaches the mind only by means of printed letters arranged in a given order.”

Cited in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, vol. 2: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1970), 110.

In a 22 February 1860 diary entry Delacroix commented on Realism:

“Realism. Realism should be described as the antipodes of art. It is perhaps even more detestable in painting and sculpture than in history and literature....

A mere cast taken from nature will always be more real than the best copy a man can produce, for can anyone conceive that an artist’s hand is not guided by his mind, or think that however exactly he attempts to imitate, his strange task will not be tinged with the color of his spirit? Unless, of course, we believe that eye and hand alone will suffice to produce, I will not say exact imitations only, but any work whatsoever? For the word realism to have any meaning all men would need to be of the same mind and to conceive things in the same way.

For what is the supreme purpose of every form of art if it be not the effect? Does the artist’s mission consist only in arranging his material, and allowing the beholders to extract from it whatever enjoyment they may, each in his own way? Apart from the interest which the mind discovers in the clear and simple development of a composition and the charm of a skillfully handled subject, is there no moral attached even to a fable? Who should reveal this better than the artist, who plans every part of the composition beforehand in order that the reader or beholder may unconsciously be led to understand and enjoy it.”

cited in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, vol. 2: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1970), 121-2.

Michèle Hannoosh notes Delacroix’s singularity as a writer about art:

“Delacroix was one of the few painters ever to write substantially on art. The importance of the Journal [diaries] and the projected Dictionnaire des Beaux-Arts in this respect cannot be overestimated: no other artist, not even Leonardo, left such extended and substantive discussions of the arts as he did of painting, sculpture, photography, engraving, architecture, in addition to music, theater, opera, and of course literature. No other artist ever reflected so extensively on the theoretical relations between the different arts, or linked this reflection to his own writing about them.”

Michèle Hannoosh, “Delacroix as Essayist: Writings on Art,” in Beth S. Wright, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Delacroix (Cambridge, UK-New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 154.

The French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) considered his contemporary Delacroix underappreciated:

“Delacroix is decidedly the most original painter of ancient or of modern times. That is how things are, and what is the good of protesting? But none of Delacroix’s friends, not even the most enthusiastic of them, has dared to state this simply, bluntly and impudently, as we do. Thanks to the tardy justice of the years, which blunt the edge of spite and shock and ill-will, and slowly sweep away each obstacle to the grave, we are no longer living at a time when the name of Delacroix was a signal for the reactionaries to cross themselves, and a rallying-symbol for every kind of opposition, whether intelligent or not. Those fair days are past. Delacroix will always remain a somewhat disputed figure – just enough to add a little luster to his glory. And a very good thing too. He has not lied to us like certain thankless idols whom we have borne into our pantheons. Delacroix is not yet a member of the Academy, but morally he belongs to it. A long time ago he said everything that was required to make him the first among us – that is agreed. Nothing remains for him but to advance along the right road – a road that he has always trodden. Such is the tremendous feat of strength demanded of a genius who is ceaselessly in search of the new.”

Charles Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1845,” Art in Paris 1845-1862. Salons and Other Exhibitions, Jonathan Mayne, trans. and ed. (Oxford: Phaidon, 1965), 3.

Web resources

smarthistory: Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People

Readings

Allard, Sébastien. ‘Dante et Virgile’ aux Enfers d’Eugène Delacroix. Paris Réunion des musées nationaux, 2004 (in French)

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Nina. French Images from the Greek War of Independence 1821-1830: Art and Politics under the Restoration. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989

Barthélémy, Jobert. Delacroix. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998

Baudelaire, Charles. Eugène Delacroix, His Life and Work. New York: Lear, 1947

Britsch, F. “Destruction and Creativity – Eugène Delacroix’s Massaker von Chios,” Pantheon, vol. 55 (1997): 136-50 (In German)

Brown, Roy Howard. “The Formation of Delacroix’s Hero between 1822 and 1831,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 66, no. 2 (June 1984): 237-54

Castandet, C. “A French Masterpiece: Dante and Virgil in Hell : Delacroix’s First Painting Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1822,” Conaissance des Arts, vol. 616 (May 2004): 104-7

Delacroix, Eugène. The Journal of Eugène Delacroix. Hubert Wellington, ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980

Delacroix, Eugène. Selected Letters, 1813-1863. Boston, MA : MFA Publications, 2001

Djebar, A. Women of Algiers in Their Apartment. Charlottesville, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1992

Dorbani-Bouabdellah, Malika. Eugène Delacroix: Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement. Paris: Musée du Lourvre editions, 2008 (In French)

Fraser, Elisabeth A. Delacoix, Art, and Patrimony in Post-Revolutionary France. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004

Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. “Blood-Mixing. Ottoman Greece. Delacroix’s Massacres of Chios, 1824,” in Extremities. Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2002, 237-317

Mora, Stephanie. “Delacroix’s Art Theory and His Definition of Classicism,” Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 34, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 57-75

Pointon, Marcia. “Liberty on the Barricades: Woman, Politics and Sexuality in Delacroix,” in Naked Authority. The Body in Western Painting 1830-1908. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990, 59-82.

Porterfield, Todd. “The Women of Algiers,” in The Allure of Empire. Art in the Service of French Imperialism 1798-1836. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998, 117-41

Roger-Marx, Claude. Delacroix. New York: George Braziller, 1971

Rubin, James H. “Delacroix’s Dante and Virgil as a Romantic Manifesto: Politics and Theory in the Early 1820s,” Art Journal, vol. 52, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 48-58

Sérullaz, Arlette. Eugène Delacroix: La Liberté Guidant le people. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2004 (in French)

Wright, Beth S. ed., The Cambridge Companion to Delacroix. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001

Images

From 1857 to 1863 Delacroix lived in the charming Place Furstenburg, Paris (6th arrondissement). Entrance from Place.

From 1857 to 1863 Delacroix lived in the charming Place Furstenburg, Paris (6th arrondissement). Apartment building entrance.

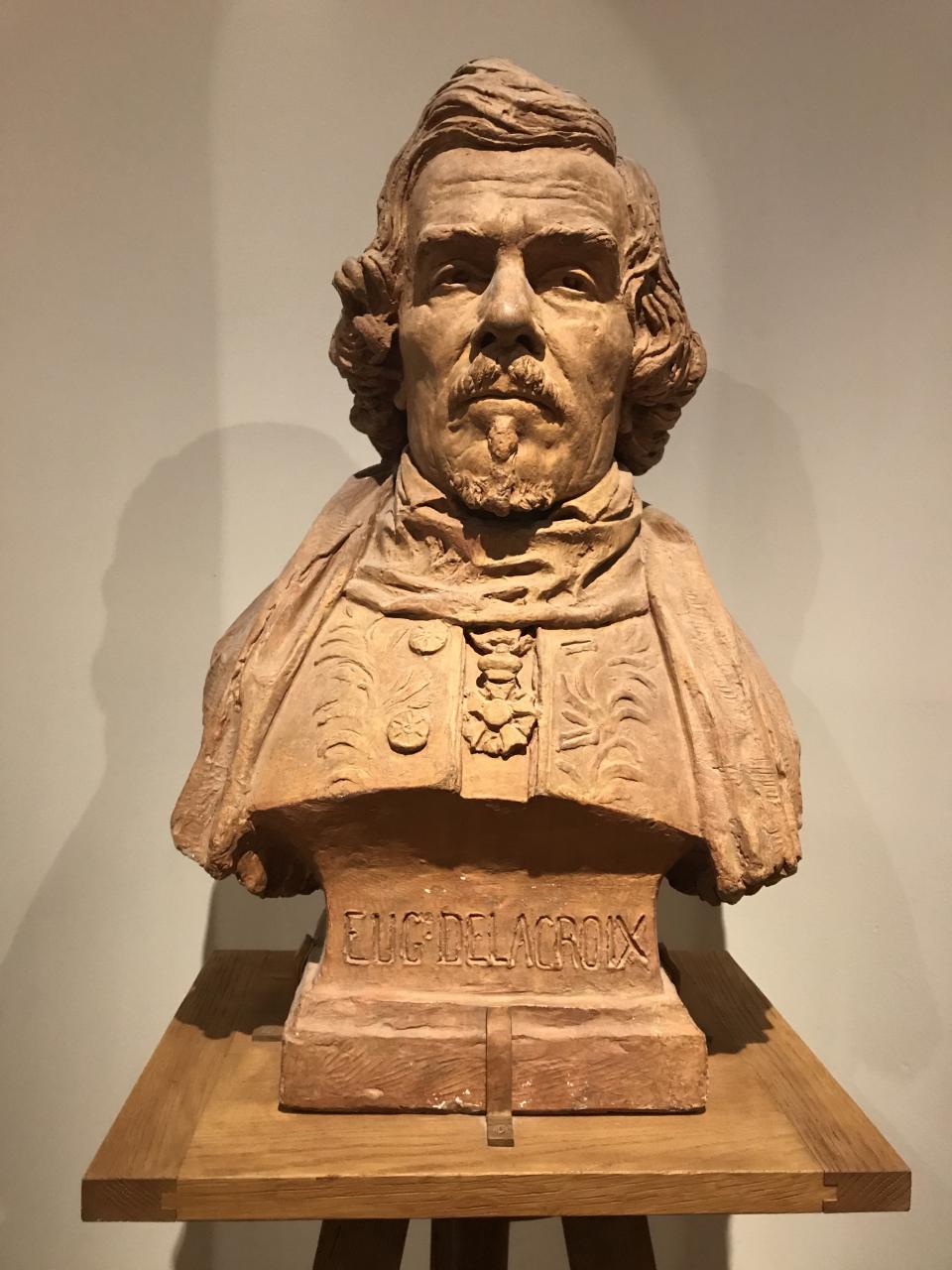

Jules Dalou, Delacroix Memorial, 1890 (Luxembourg Garden, Paris). Figures at base represent Time, Glory & Genius of the Past.